Continual Improvement : CI / CD at Tyler Technologies, Data & Insights Division

-

- Posted: 26 Sep 2019

- Category: Build, and, and Deployment

- Tagged: build, deployment, jenkins, continuous integration, continuous deployment, and scaling

-

Related Posts

- A Move to Main Branch

- Peter Moore on 13 Oct 2021

- Time Series Analysis with Jupyter Notebooks and Socrata

- rlvoyer on 07 Oct 2019

- Welcome (back) to our blog!

- helenasw on 14 Aug 2019

Continual Improvement: CI/CD at Socra..er Tyler Technologies, Data & Insights Division

Jenkins in the Closet

Our Engineering organization has a long, and storied history with CI / CD in our division. It starts well before I arrived at Socrata in 2014 (during the antediluvian period aka 2013) when it was decided that ‘Hey, what we could really use is some regular end-to-end testing’. Contractors were hired and soon this testing was underway at Socrata, a scrappy startup running on gumption and a dream in the heart of Seattle’s Pike Place neighborhood. The testing took the form of a series of automated suites based on the Cucumber framework and a Jenkins server which was running on a server under a desk in the Lead Contractor’s apartment. Things were pretty lean back then.

Soon end-to-end testing became a much more important part of the process that we relied upon for shipping our code. We brought the test server into our office and shoved it into an unobtrusive broom closet in the corner. Our test infrastructure grew to include a blade server for Windows VMs and an Ubuntu 12.04 server that hosted the new shiny Jenkins server and its associated Linux based testing. Things were better, faster and more reliable, but they were still pretty slapdash.

We chugged along this way for most of a year. We shipped software based on those cucumber test results and almost all was well. But like the flow of time, software and its infrastructure are never constant and it was decided that now was the time to completely overhaul our infrastructure. It was time we cast off from Azure and our physical data-centers where Engineers must change disks and speak soft assurances to temperamental machinery. It’s 2014 now, almost 2015 really. It’s time for AWS.

Jenkins in the Cloud

We began a great quest to move the entire business to AWS and Jenkins was in the vanguard of that effort. We began converting Jenkins infrastructure by leveraging the following important elements:

First we created a chef cookbook for our Jenkins server and began provisioning it with all the build toolchains and plugins that existed on the Jenkins in the closet. Its was a hodgepodge of Ruby and Scala, Java and Python, Docker and Rails. Then we migrated our jobs, one by one, from our Jenkins in the closet to our Jenkins in the cloud, making sure that each worked.

We completed our move to the cloud and wound up with two AWS based Jenkins servers on EC2 instances. Why two? Well, it turns out our growing testing and build processes put together on a single node quickly overwhelmed the poor server and revealed a particularly nasty network driver bug present in AWS M4 EC2 instances. Under high load, the driver would, on occassion, get overloaded, fall over and not be able to get back up and running until you rebooted the server. As our test frequency increased, this became more and more of a problem. To avoid this problem, we split the load between a build server (handling all build-type jobs) and test server (handling all automated testing jobs).

Even with our jobs split into two servers, the load continued to grow and our poor servers soon became overloaded again during peak development times. The servers were so overloaded that they would fail and need to be stopped and restarted in the AWS console several times a week. Yuck! Later, we were able to compile a new network driver into the kernel that didn’t have this issue as a temporary solution. It was only when M5 EC2 instances (which use a different network card and thus different driver) became available that we were able to resolve the network load issue permanently.

Even after solving this issue, we still needed to scale our Jenkins servers as the daily load continued to grow. We could make them bigger (truly humunguous in fact), but there is an upper bound (in both capacity and cost) and there are also fringe resource collision issues as the parallelism of tests grows on a single host. For example, several of our test suites drive headless browsers for UI testing. We found that the driver that runs those browsers starts to show performance issues when it must manage more than a few dozen active connections simultaneously. This drove up our test times during heavy load times. In addition, heavily parallelized scenarios revealed some process shutdown issues that would essentially start orphaning driver threads over time, requiring administrative intervention or a reboot.

Obviously we couldn’t scale up. Our best option was to scale out. Enter Jenkins Workers, stage left.

Go Forth My Children And Scale

Jenkins is probably the most pervasive CI / CD solution in the world. Hundreds of thousands of deployments and millions of user make a pretty big community. And since the customers of Jenkins are developers by and large, they are able to give back in a virtuous cycle to the Jenkins ecosystem. The Jenkins community is huge and active, and Jenkins encourages this by being highly extensible through the plugin capabilities that the core system provides.

Plugins are the lifeblood of the Jenkins system. There are thousands of these plugins maintained by community members which provide immeasurable value to the community. One of these plugins is the EC2 plugin. This plugin allows Jenkins to interact with AWS to manage worker EC2 nodes and send them work in a dynamic way. This enables Jenkins to scale out dynamically and provide nearly limitless execution capability. The limiting factor when using this plugin really comes down to a question of budget.

So we decided to solve our scalability problems by converting our jobs to running on workers. Easy Peasy. Well, not exactly.

First, we created a chef recipe for the workers which provisioned it for each of the toolchains and software tools we use for building and testing our projects. A partial list includes:

This is a partial list. With this chef recipe created, we were able to use the packer tool to build an AWS image (AMI) from this cookbook. Now we have a provisioned worker ready to work right? Not yet. We still need to give this worker permssions to interact with the systems we use internally as we build our projects. To do that we configure the worker to interact with (among others) the following 3rd party services:

Complicating the worker’s interaction with these services is the requirement that we not store credentials on the AMI at rest. Our solution for credential management on the Jenkins server node isn’t available to the built AMIs, so we ended up using a homegrown solution to interact with the encrypted AWS KMS secure storage service from anywhere. We can use this KMS wrapper to pull files to the worker at boot time from within the AWS cloud. We leveraged the boot script capability of the worker configuration and made it pull down and apply the security credentials and configuration files at boot time. These workers are short-lived so the credentials are effectively ephemeral. Problem solved.

So, after adequately provisioning our worker AMI we now have two recipes; one server and one worker that we will use to scale Jenkins.

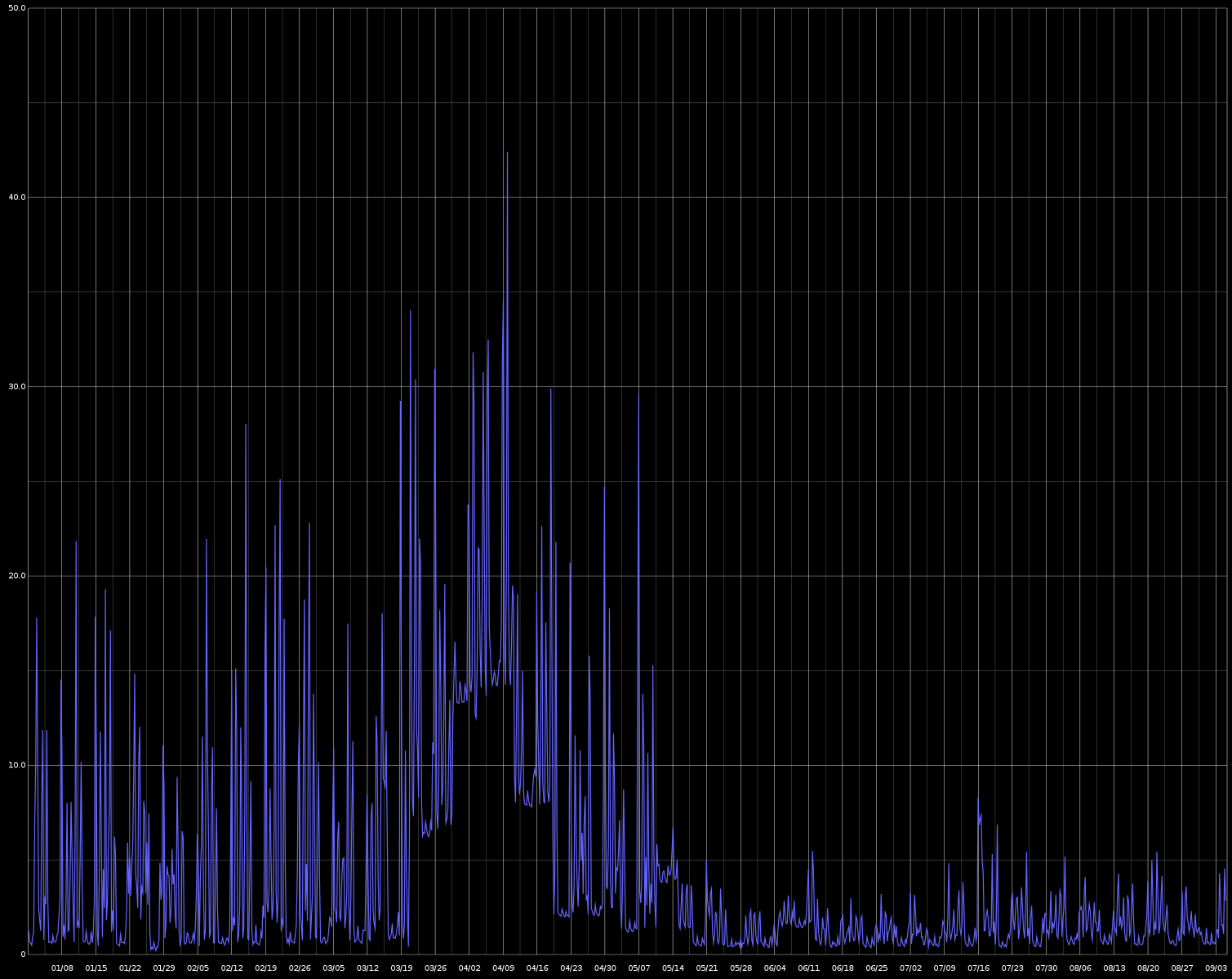

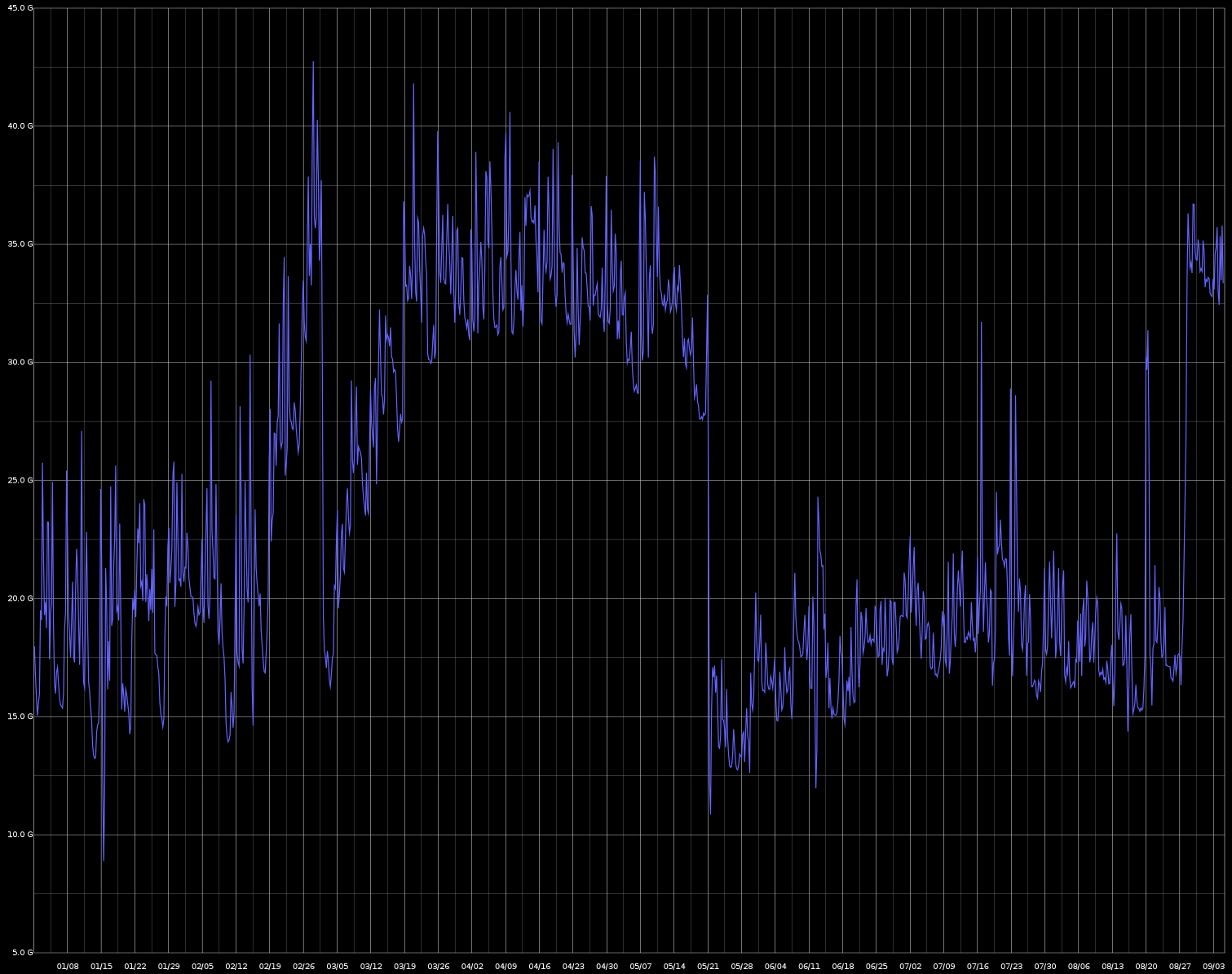

Now, after verifying the workers with some testing, it was time to start migrating our build jobs to the workers. This was a voyage of discovery. We found significant configuration requirements that weren’t documented when we initially created the worker. But we used each discovery to formally capture these requirements and place them in the worker recipe such that it handles the requirements of each job and is repeatable. This migration process also helped us realize when we were solving a problem more than once or in diverse ways. Going through this process allowed us to streamline the jobs to be more homogeneous. By forcing our jobs to work on disposable hosts we encourage job owners to make their jobs self-sufficient. It was a long process taking months (in fact is continues to this day) but we pretty quickly began to see the benefits of this work. By tackling our most resource intensive jobs first, we were able to see immediate impacts on the server; loads dropped, server memory related test failures became almost non-existent. Tests run in relative isolation no longer needed to contend with other jobs for shared local resources. The server was no longer the bottleneck. Here are some graphs that show the effects. See if you can spot when the workers really started getting going.

System Load Averages (January 2019 - September 2019)

System Memory Utilization Averages (January 2019 - September 2019)

After a few months of effort, most of the jobs we considered “heavy hitters” had been moved to workers. But we had this other server? This test server. What should we do about that?

Well, again, we made sure that the worker was provisioned with all the tools it needed for the tests to run on it properly. Then we began moving jobs from the test server directly to workers. No additional load hit the server and our worker utilization continued to grow. Soon, we were in a position where we could turn off the Jenkins test server and truly have only one Jenkins server running all builds, deploys and tests.

These days, the build server is now becoming a job scheduler. Through configuration of the EC2 plugin we can define pretty robust behavior of our workers. We can set how many workers are allowed, how long they live, what types of EC2 nodes to use, how many jobs they can execute simultaneously and which jobs, etc…

We anticipate that in the next few months, as we finish migrating all jobs to workers, we will be able to start reducing the EC2 host size of the server itself (its currently a C5.4xlarge, costing us quite a bit each month). We will start by reducing its size in half, profiling the new sized node and then progressing to smaller nodes as seems reasonable. The hope is that it will truly become just a job scheduler. Job execution will live on the scalable, disposable workers. We aren’t done yet with this work (lots of jobs still to convert) but we have a much a happier development team and a much relieved ops team. Achievement unlocked!